The Luxury Trade of 17th-Century Antwerp

By Brandon Finney ’15 (Vic.)

“The tapestry is important because it’s an imposing presence in the Hall that is the heart of the College,” says Sylvia Lassam, Trinity’s Rolph-Bell Archivist. “It’s compelling because of its scale, its age, and the fact that it’s always been there. I believe, as a non-graduate, that people respond to the fact that the physical part of Trinity is always essentially the same, even though in many ways it changes constantly. Strachan Hall and the tapestry will always be a link to their time at Trinity.”

TRACING A RICH ANCESTRY

Beyond its life at the College, little else was known about the tapestry. In fact, many of Larkin’s donations were never catalogued with any details of provenance. The work was probably purchased during one of his trips abroad, and based on its appearance it was thought to be a product of the Netherlands circa the 17th century. A recent exploration of comparative works and historical documentation has now revealed the tapestry’s origins and authorship.

The tapestry depicts the biblical story of King Solomon meeting the Queen of Sheba. It was designed as one part of a larger eight-piece suite of tapestries depicting the stories of King Solomon. Several other examples of the same design, and others in the suite can be found across the world in Canada, Italy, England, Wales and Sweden. Historical records suggest that Trinity’s tapestry was woven circa 1660-1703 by the Wauters Firm, one of Antwerp’s most successful weaving firms of the late 17th century. Records further confirm the designer as the Flemish artist Abraham van Diepenbeeck, a pupil of the celebrated Peter Paul Rubens.

VALUABLE INSIGHTS

Alumni and affiliates of the College are not the only readers who should take an interest in the tapestry; now that its origins have been identified, the work can offer viewers a compelling insight into one of the largest and most luxurious industries of 17th-century high culture. These textile works were the most treasured artifacts of Europe’s richest aristocracy—immediate symbols of power and wealth, and incredibly valuable assets. Estate records indicate that one tapestry alone could command more than an aristocrat’s entire collection of paintings by the Old Masters.

During the 17th century the Netherlandish tapestry industry reached its pinnacle, with major producers in Antwerp and Bruges exporting their works across Europe to major cities like Vienna, Rome, Stockholm, Lisbon and London. The economic prosperity of Antwerp and Bruges supported the development of the complex economic systems necessary to produce what were at the time the single most expensive art objects one could buy.

Much like buying a car today, patrons would order tapestries from a “floor model”—a drawing, painting or finished weaving—from a central dealership called the Tapissierspand (The Tapestry Hall). Tapestry dealers ran workshops that sold works out of the Tapissierspand marketplace. These dealers would commission artists, like Diepenbeeck and Rubens, to create a series of tapestry designs on speculation.

LABOUR-INTENSIVE ART

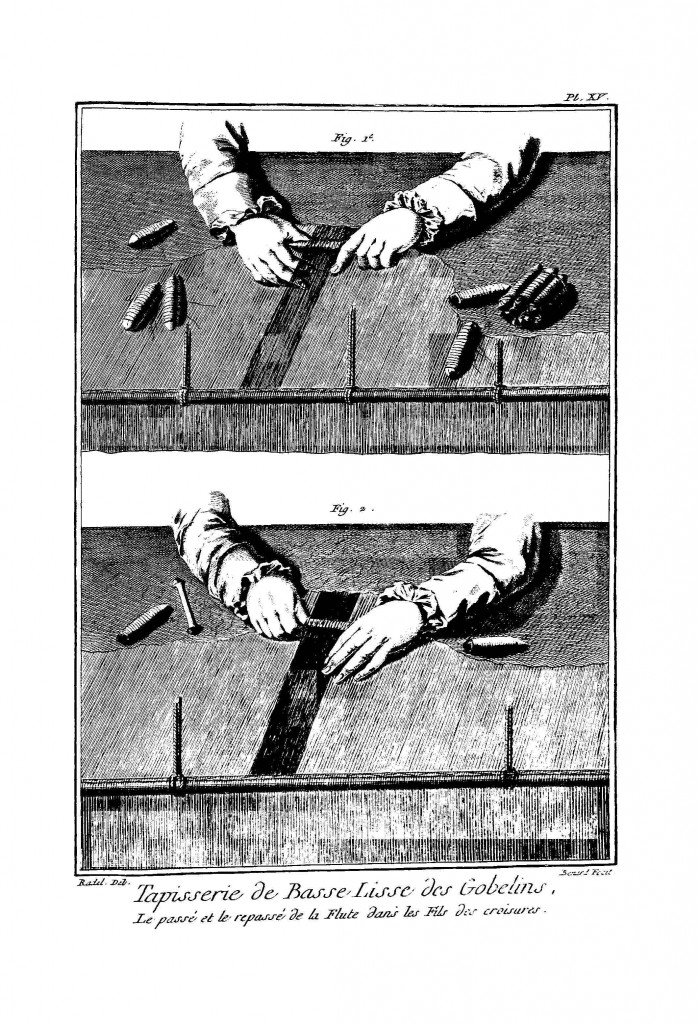

Tapestry works are created by stretching long, woollen warp cords across a loom. A design is placed behind the warp and a weaver translates this with coloured silk weft threads woven in and out of the warp. Hand weaving is an extremely timeconsuming process—works like the Trinity College tapestry would have taken a single weaver more than two years to complete. To speed production, the Trinity tapestry was made in two pieces concurrently and then stitched together— this process is evident in the vertical seam running down the middle of the work. Employing two looms with multiple weavers meant the tapestry could be finished in a matter of months.

Tapestry works are created by stretching long, woollen warp cords across a loom. A design is placed behind the warp and a weaver translates this with coloured silk weft threads woven in and out of the warp. Hand weaving is an extremely timeconsuming process—works like the Trinity College tapestry would have taken a single weaver more than two years to complete. To speed production, the Trinity tapestry was made in two pieces concurrently and then stitched together— this process is evident in the vertical seam running down the middle of the work. Employing two looms with multiple weavers meant the tapestry could be finished in a matter of months.

FADED GLORY

Unfortunately, because of the materials and techniques used to construct textile works during the late 17th century, the Trinity College tapestry shows advanced signs of deterioration.

Like most works of the period the Trinity tapestry is woven primarily in silk. These fibres are extremely sensitive to light, and over time, will undergo photodecomposition. Once prized for their shimmering brilliance, the silk fibres are now dusty and brittle, some disintegrating with the touch of a hand.

Interestingly, these condition issues can also be understood as symptomatic of changing tastes in art. By the end of the 17th century, time-honoured Medieval and Renaissance designs were passé. The new vogue was for monumental tapestries that resembled the popular Baroque painting style of Peter Paul Rubens. In order to reproduce the painterly effects of Rubens’ designs, weavers had to employ new and experimental dyes. These dyes have proved to be the undoing of almost every tapestry from this period— chemical mordants (colouring fixatives used to set the dyes) employed in the new dyeing process have actually further accelerated the chemical degradation of once-pearlescent silk fibres.

Further problems have also arisen due to the weaving technique employed. Weft threads are not continuous across the entire length of the work; rather, they are tied off at the outlines of forms and colours. Where two discrete sections of weft meet, a slit is formed, which would be sewn shut. Unfortunately, over time these slits have destabilized the tapestry as gravity and degradation of the thread fibres cause them to reopen.

As a result of these intrinsic flaws and centuries of light exposure, the Trinity tapestry is now a faded image of its former glory. In an effort to conserve the tapestry, the work was cleaned and extensively reinforced with fine lines of white stitching in 2012.

THE VALUE OF TAPESTRY

Readers may be interested in the monetary value of such a work. Its scale and age might suggest that it would command a great price at auction. In reality, works like the Trinity College tapestry, because of their size and fragility, are often not worth much on the art market.

However, as a prominent feature of the College and as an artifact representative of a larger history, the Strachan Hall tapestry is invaluable. Trinity has done the public a great service by investing the necessary funds to have the work professionally conserved and continually displayed—it’s not often we get to interact with works like this in Canada, where such artifacts are often stored in over-glazed museums or locked away in storage vaults.

The above article is an abridgment of the research I did for a fourth-year Material Culture course at Victoria College. I would like to thank to Dr. Nicole Blackwood for suggesting the Trinity tapestry as a topic, and for advising my research. Brandon Finney is a fourth-year student at the University of Toronto. He studies Art History, and has an interest in pursuing a career in Fine Art Conservation.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.