How I narrowly escaped a war zone in Liberia—and returned to help during the Ebola epidemic

By Dr. Kathryn Campbell Challoner ’70

By Dr. Kathryn Campbell Challoner ’70

In early 2003, tensions that had been growing in Liberia for several years between then-President Charles Taylor and two opposition groups reached a boiling point. Fighting between government troops and rebel insurgents increased to the point that rebel forces controlled two-thirds of Liberia by mid-June 2003. With rebels advancing on the capital, Monrovia, international staff of the UN and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) were forced to evacuate. Kathryn Campbell Challoner ’70 was among them.

The cell phone rang. It was the American Embassy calling me into “Safe Haven.” It was July 2003, and health care workers and desperate refugees were under siege in Monrovia, Liberia.

“The rebels have crossed the bridge and are entering the city although the State Department is trying to intervene—you must go immediately to the Embassy.”

We would have to cross a war zone. Benedict, my medical student, and I hurried into our medical outreach van. We were in Monrovia working with the Episcopal church.

The first two barricades were manned by child soldiers with machine guns who were clearly under the influence of something chemical, and easy to bribe. The third barricade was manned by the ATU (Anti-Terrorist Unit of Charles Taylor). They motioned us down an alley with their guns.

Benedict, who was in the driver’s seat, said this wasn’t good—I rather agreed with him—and then added that one didn’t come out from alleys in Monrovia alive.

He pretended to turn the van, and then suddenly straightened and crashed the barrier. The ATU fired and missed— we were now in the war zone and bullets were flying around us at an unarmed population.We finally reached the gates of the Embassy. Benedict pushed me into the arms of a Marine and dived for cover.

Four days later, I was evacuated by a Black Hawk helicopter with other rescue personnel to Sierra Leone. Armed Marines guarded the windows as gunshots rang out from the ground beneath us. I remember it was raining. As I looked out the window at the carnage below, I vowed I would be back.

Many trips and many years later I was standing in the middle of a small rural village in Northern Liberia that had been devastated by Ebola.

I was one of many health care workers who had responded to serve in West Africa to provide critical health care during the Ebola epidemic of 2014-2015. Benedict, now a full-fledged physician and one of his country’s leaders, had brought me here with a truck loaded with rice, school supplies, and messages of love and concern for the people.

“We have built a school,” we said, “and we want you all to come. Everything is free. You are loved and we are here to invite you to come.”

“We have built a school,” we said, “and we want you all to come. Everything is free. You are loved and we are here to invite you to come.”

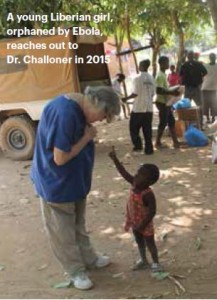

A tiny girl wandered up to me. She had never spoken and had large, hurt eyes and clenched fists. Then suddenly she reached up to me with her finger to try to touch me and to speak.

Here Dr. Benedict B. Kolee and I would build a community of education and love—a school, a health care centre, and dormitories if necessary for the homeless children.

Here at ground zero of the epidemic’s entry to Liberia we would bring hope (“Ketobaye”) so that these little ones would one day be able to tell their stories of this horror that had devastated their villages, families and lives.

Dr. Kathryn Campbell Challoner obtained her BSc at Trinity College and her M.D., Magna Cum Laude from the University of Ottawa. She completed two residencies (Family Practice at Toronto General Hospital and Emergency Medicine at the LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles). She earned her Master’s in Public Health designation at the University of Southern California, her diploma in Tropical Medicine from the Gorgas Institute in Peru, and is a Fellow of the American College of Emergency Physicians. She has taught and published widely, and is the recipient of numerous community and humanitarian awards. She has been married for 46 years to Dorian, an aerospace engineer, and they have three children. She is a lifetime member of an Anglican Religious Order (A Tertiary of the Society of St. Francis).

In January 2015, Dr. Challoner retired from her full-time position as a member of Attending Staff and Faculty in the Department of Emergency Medicine at LAC+USC Medical Center to respond to the Ebola crisis in West Africa. She has established three “arms of support” through her ongoing work in Liberia:

• She maintains and runs a medical scholarship program, with administrative support from the Third Order Society of St. Francis and outside donor support that pays all tuition costs for BSc degrees in Nursing, MSc degrees in Public Health, and Health Administration and MD degrees.

• She and her husband, along with other private donors, provide funding for medical equipment, medical supplies and teaching symposiums to hospitals in Liberia, especially Phebe hospital (an Episcopal/Lutheran hospital) in rural Liberia.

• She is actively working on an Ebola orphan project in Lofa County at Bolahun—“ground zero” of the Ebola epidemic in Liberia. She and others have established a free school, health care, and support for the Ebola orphans of that area. The school is on the former grounds of the Anglican Order of the Holy Cross in Northern Liberia.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.