The College’s first-ever student experience survey yields fascinating insights into today’s students

by Cynthia Macdonald

Illustration by Karsten Petrat

Tradition and change. Sooner or later, every Trinity student faces the competing demands of these two very different masters. And as a brand-new student survey reveals, that challenge may be greater today than ever before.

The survey, a historic first for the College, was administered in February of this year. “The main impetus came from the students; they wanted this to be their big project for the year,” says former Dean of Students, now Assistant Provost, Jonathan Steels. “It was important for them to see where the community sits in a historical context.”

Aditya Rau, last year’s Male Head of Arts, affirms that the 76-question study was designed to canvas current opinions on a variety of issues pertaining to undergraduate life at Trinity, and to spark “informed and meaningful discourse—discourse that I’m sure will shape policy and the student experience for years to come.”

AN EVOLVING COLLEGE

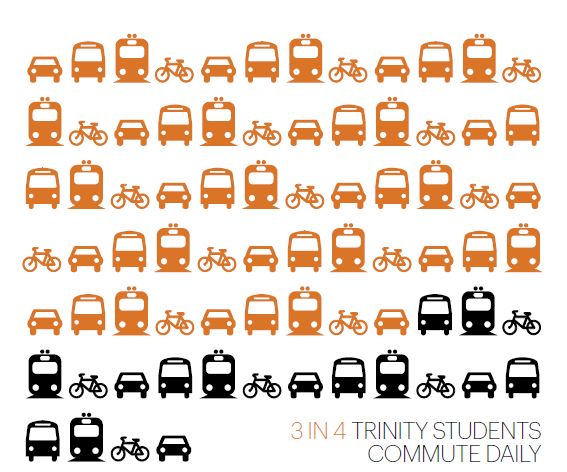

Even before the survey, it was obvious that the Trinity of 2015 has come a long way from its origins in 1851. Once an all-male bastion, its enrolment is now 62 per cent female. Visible minority students account for almost half the total survey respondents, and three in four students now commute instead of living in residence. Trinity’s changing composition has invariably had an impact on its beloved traditions—from High Tables, frosh events, and formal dances like Saints and Conversat; to gowning in, pooring out, and everything in between.

QUESTIONING THE ROLE OF TRADITIONS

Assistant Provost Steels says such traditions remain deeply attractive to students: they provide links to the past, and form the foundation on which Trinity’s unique and enduring social life is built. But over the years, some traditions have been phased out, while new ones have been introduced. Still others have been reimagined to fit better within a contemporary context. What the survey reveals is that modern students are eager to preserve the old ways, while simultaneously laying the ground for a bold new future.

Assistant Provost Steels says such traditions remain deeply attractive to students: they provide links to the past, and form the foundation on which Trinity’s unique and enduring social life is built. But over the years, some traditions have been phased out, while new ones have been introduced. Still others have been reimagined to fit better within a contemporary context. What the survey reveals is that modern students are eager to preserve the old ways, while simultaneously laying the ground for a bold new future.

“The very first question we asked was, to what degrees do Trinity’s history and traditions factor into your decision to come here?” says Steels. “And we got overwhelmingly positive responses to that question from all students. They say this all the time to me at meetings—history and traditions matter! But we need to take a fair, inclusive approach to them. Understanding some of the underlying inequities will help us better move some of these practices into the modern day.”

Do students think Trinity is as welcoming and inclusive as it could be? And can its cherished traditions be preserved, while recognizing the changing needs of a modern population?

A survey of every registered student seemed like a good way to find out. After all, every student is required to pay student fees and is eligible to participate in governance via the Trinity College Meeting (TCM), but not everyone does; student governors reasoned that the votes of a few might not truly represent the opinions of the many. Also, “we wanted to get a vibe of what students were feeling in an anonymous way, because we didn’t want anyone to feel that they might be ostracized for expressing their opinion,” says Tina Saban, last year’s Female Head of College.

A BROAD SCOPE

Inspired by a shorter survey on alcohol use, which elicited some 700 responses and was conducted five years ago, the TCM’s six Heads initially centred their questions on gender. They wondered: was Trinity’s long history of male-female segregation at the level of governance, residences and events still valid in the modern era?

But the survey mandate eventually broadened to include questions about the impact of mental health concerns, the difficulties facing commuter students, the continuing value of specific traditions, and many others. It also sought extensive demographic information, to capture an accurate picture of Trinity’s socioeconomic and ethnocultural composition.

After spending what Saban calls “countless hours” working with the administration to draft and re-draft the document, it was issued to enthusiastic response. “We had 500 respondents out of a total of 1,800 registered students respond to it, with an equal split across all four years,” says Steels. “Surveys often have a response rate of 10 per cent, so a response rate of 28 per cent is great. It allows us to have a good degree of confidence in our analysis. It also allows us to break it down into specific demographics, to see whether we need to target the concerns of particular groups.”

MENTAL HEALTH TOP OF MIND

While detailed analysis of the data is not yet completed, some general observations can be shared and are already being used to spur some of the changes students have asked for. Mental health, for example, is a major area of focus at universities across North America, and figured in this survey as well. “There’s been a lot of work to reduce stigma around this,” says Steels, “and there’s no question that students talk about it all the time. They’re very concerned about the need for support, and about developing resiliency.”

In any discussion of mental health, many factors come into play. Aside from the potential isolation caused by socioeconomic, ethnocultural and gender factors, among others, there is also the pressure to do well. “We have very high achieving students, with great goals in mind. The result is that anxiety is very high,” says Steels. “This is a really good area for focus group work in the fall, to try to understand the problem better.”

“Mental health and overall student wellness are key priorities for the College going forward,” says Trinity Provost Mayo Moran. “We believe strongly that supporting students goes beyond providing an excellent academic experience— it must extend to the healthy development of the full person.”

ECONOMIC DISPARITY

The survey also revealed that many students do not come from the kind of economically privileged background that was once very much associated with the College; financial struggles are common, and often affect students’ ability to fully participate in activities.

The survey also revealed that many students do not come from the kind of economically privileged background that was once very much associated with the College; financial struggles are common, and often affect students’ ability to fully participate in activities.

“Two of our largest events, Saints and Conversat, are quite expensive,” says Nathan Chan, a third-year student and TCM’s incoming deputy auditor for 2015-2016. “There’s been some resentment about that. A fund has been created [called the “Student Accessibility Levy,” it pools $12 from every student] so that students without economic means can attend these events. That was a direct result from the student experience survey.”

ENGAGING COMMUTERS

Saban says that in the survey, commuter students (who may be at a financial disadvantage) also expressed difficulties they had in connecting with their peers. “There are a lot of students who live off campus who simply can’t participate, for a variety of reasons,” she says. “Things like commuting time, or having to split time between part-time work and studying.”

Saban says that in the survey, commuter students (who may be at a financial disadvantage) also expressed difficulties they had in connecting with their peers. “There are a lot of students who live off campus who simply can’t participate, for a variety of reasons,” she says. “Things like commuting time, or having to split time between part-time work and studying.”

Steels adds that, “Only a quarter of our students live in residence, so we can definitely do a lot more to engage commuting students.” According to another recent survey—the National Survey of Student Engagement—U of T has far more commuter students than other large schools in Canada: 25 per cent vs. 15 per cent. Consequently, making these students feel welcome is a key mission across the university as a whole.

GENDER IDENTITIES

Gender questions are extremely important at Trinity, something also reflected in the survey. Last fall, student concerns about a proposal to change language in the TCM’s constitution—from “Men and Women of College” to the more gender-equitable “Members of College”—failed, resulting in a tense and divided atmosphere.

“But what’s most important to recognize about that struggle,” says Aditya Rau, “are the benefits that came from it. As the year progressed, “we saw people sitting down with proponents and saying: help me to understand this better. The College was really alive with conversation—in the dining halls and the common rooms, people were talking about why this motion was important and why it needed to be pushed through.” As a community, students came together and learned from each other. In March, at a TCM with almost 200 students in attendance, attitudes had changed and the proposal passed nearly unanimously.

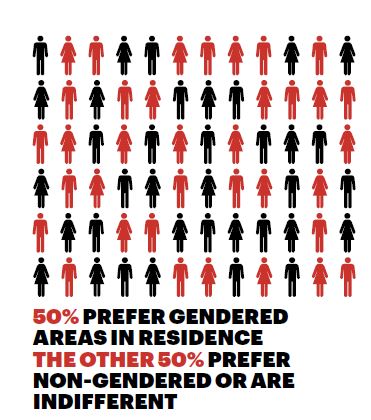

“Gender identity stood out as really interesting,” says Steels. “We saw a pretty significant number of individuals who say their assigned gender identity does not match with their gender expression.” Up to 10 percent of students fall outside the male-female binary, preferring such terms as gender queer, intersex, androgynous, trans or questioning to describe themselves.

This has already spurred significant change at Trinity, in the form of gender neutral residence spaces. Students are now allowed to choose between dress codes at High Table dinners, and some administrative language has been altered. “We find this issue is broadly impacting our practices,” says Steels.

Fourth-year history major Haley O’Shaughnessy was this year’s President of Rainbow Trinity, which represents the College’s LGBTQ students. O’Shaughnessy has worked hard to create a more equitable environment for non-binary students (such as themself). O’Shaughnessy and fellow student Iris Robin were behind the proposed change to constitutional language that reinforced the need for the survey.

But O’Shaughnessy stresses that while gains have been made, Trinity still has some improvements to make (an Equity Don, for example, is another thing they would like to see.) And even if 10 per cent strikes some as a large figure, O’Shaughnessy contends that “numbers games rarely work with equity issues, because equity issues tend to affect people who are in the minority.”

Assistant Provost Steels agrees that if even one student feels marginalized, that is one too many. But he also emphasizes the survey’s educational value. “When our community sees that certain opinions are actually shared by many of its members, that could motivate the kind of concerted effort that often results in real change,” he says, adding that it’s also critically important to help people understand equity issues, thereby encouraging a culture shift toward positive change.

QUESTIONS OF SEXUALITY

Another unexpected revelation in the survey was the large percentage of students who described themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. “Ten per cent has been the expected percentage in society, but our numbers came out closer to 20 per cent,” says Steels. “Here, Trinity scored high for being accommodating and having equitable practices. But the result underscores the importance of inclusive and diverse practices around this topic.”

EQUITY IN LEADERSHIP

In the 21st century, the most striking change on the gender front has been the high enrolment of female relative to male students. And yet these numbers are not reflected in student governance structures, which remain skewed toward male leaders. Survey results suggested that real work needs to be done here.

But Saban notes that Trinity’s oft maligned gender roles have actually had a positive effect, which should be taken into account. “If there weren’t designated head roles for women,” she says, “I can tell you that we would not see very many women in those positions.

“I know the College is doing a lot of great work to encourage female leadership,” continues Saban, who recently graduated and will be attending U of T law school in the fall. She cites the examples of panel discussions and leadership awards, as well as a special High Table for female leaders that was “totally heartwarming,” in that it provided a place for mentors to bond with aspirants. “That’s something we’re going to do every year now, which is awesome. It’s another tradition we’re hoping to create.”

SUPPORTIVE COHORT

Steels says the student-led survey is just one example of the involved, proactive character of today’s scholars. “One of the wonderful things about this generation is that they really care about each other,” he says, pointing out that Trinity students already provide peer support to those afflicted by sexual violence, substance abuse and financial problems, not to mention academic distress.

The survey will help them prioritize areas of need and uncover others—ones that they, but more particularly the administration, may have known relatively little about before.

THE PATH FORWARD

“With this knowledge, we now see far more clearly what really matters to students,” Steels says. “This will help us reach out to them further. In the fall, we’ll be encouraging much more discussion around the topics covered in the survey. We’ll convene focus groups that will help us gain an even deeper understanding of concerns, and invite everyone to share their opinions in new and different ways. The survey is just a starting point for the great work that can be done when we all come together as a community. Through this work we will continue to educate our community around the various facets of equity.”

For his part, Rau is confident about the survey’s power as a tool to inform, teach and bring about change at Trinity. “I think change always results in conflict when it’s not informed by facts—facts that can really illuminate where the College stands at the moment. Gathering that knowledge was really important. We have to think about how we can make the student experience here open to everyone.”

A tradition only earns that name over the long haul; until then, it remains a bright innovation. While still in its early days, the student experience survey may in time prove such a powerful vector for change that it takes its rightful place alongside many other honoured traditions— traditions that will surely be trimmed, tailored and talked about for many years to come.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.