Why I’m striving for a socially just Canada

By Anthony Morgan ”08

When I consider my experiences since graduating from Trinity’s Ethics, Society & Law program, I almost immediately think of a 1998 song by Canadian rap legend Maestro Fresh-Wes, entitled “Stick to Your Vision.”

On this track, Maestro reflects on his career highs and lows as a Canadian rapper who abruptly fell into relative obscurity in the mid-1990s after enjoying unprecedented success in the American-dominated market for rap music. Despite his shift to a lower-profile role, Maestro stayed committed to his vision of helping to develop an urban music industry-infrastructure in Canada—one that has helped to fuel opportunities for the creation of the next Drake, the Weeknd, or Justin Bieber.

Maestro’s song resonates with me because sticking to my vision has been so critical to the success I have enjoyed early in my legal career. While it is an evolving concept, I currently define success (at least in professional terms) as doing meaningful social justice work that I’m deeply passionate about and happy doing, with smart, dynamic and socially conscious people.

The “vision” I have stuck to, which has allowed me to enjoy success as I have defined it, is of using my skills, opportunities and education to support the advancement of racial justice and equality for people of African descent in Canada. This became my vision because by the time I was in my late teens, I realized that I enjoyed a level of opportunity and access not common to people from my community. I decided to turn this recognition into a responsibility to commit to advocating for the freedom and well-being of Black people. I also adopted this responsibility as an expression of pride in my history and heritage as a person of African descent.

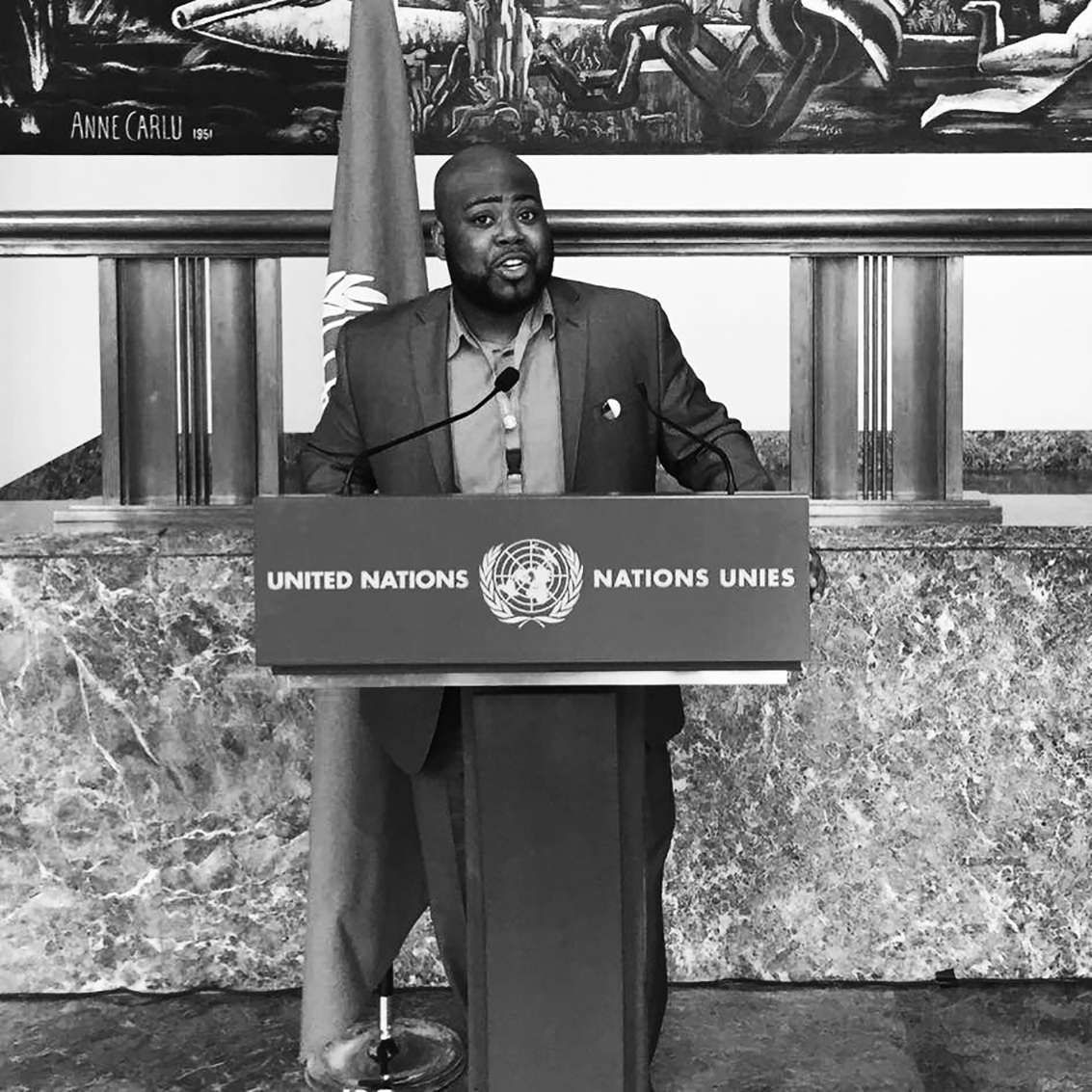

I have been a lawyer for only three years. However, sticking to my vision has enabled me to do work that has led me to appear before the Supreme Court of Canada. In November 2014, I served as co-counsel in a successful intervention to strike down discriminatory mandatory minimum sentencing for illegal gun possession in Canada. I have also participated in sessions of United Nations human rights committees, contributing to two civil society reports. The latest of these, The Blackening Margins of Multiculturalism, was published in February 2016. After I presented it to the UN Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights in Geneva, Switzerland, the committee made numerous recommendations on what Canada should do to enhance the well-being and life circumstances of Blacks in Canada.

My chosen career path has also allowed me to emerge as an authority and frequent media commentator on racial justice issues facing Blacks in Canada. Among the issues on which I’m most frequently consulted are the over-representation of African Canadians within the criminal justice system (from police interactions to prisons); statistics on police use of lethal force; the child welfare system; academic streaming, suspension and expulsion data in Ontario schools; and issues related to African- Canadian poverty, unemployment and socio-economic exclusion in Canada. Since late 2014, the most publicly discussed matter within this set of issues is a police practice known as “street checks” or “carding.”

While there is no official definition of carding, it is generally understood to be the practice of police officers stopping, questioning, documenting and storing the information of civilians who are not suspected of being involved in a crime or under investigation for being connected to an offence. This practice might sound relatively benign, but what makes it so controversial is that in every Canadian city and region where data was collected to indicate the perceived racial background of the individuals who are carded, it has been revealed that racialized people, and most especially Black men, have overwhelmingly and consistently been the primary targets of this practice. In locations where Blacks are not identified as the primary target of carding, Indigenous peoples are the primary targets.

For example, in 2012, a Toronto Star analysis of police data from 2008 to mid-2011 discovered that the number of young Black men carded was 3.4 times higher than the population of young Black men in Toronto. It is important to note that there is simply no evidence that Black people actually commit more crimes than non-Black people and that carding is not limited to policing “high-crime” areas. In fact, Toronto Star data revealed that in high-income Toronto neighborhoods with minimal to racial diversity, Blacks were even more likely to be carded.

It’s amazing now to think that there was a time when carding was an entirely foreign concept to people living outside of Toronto’s most economically challenged and racialized communities. When I first began speaking about it, I got a lot of pushback, dismissal and diminishing of the issue. But as I grew as a lawyer and advocate I drew on the lessons I learned at Trinity, where I was fortunate to have classmates and professors who respectfully and thoughtfully engaged in our discussions about anti-Black racism, helping me strengthen my thinking and speaking abilities. Those skills helped me in my early days of educating others about the carding issue, as I continued to think of new ways to articulate the points I was trying to make.

After a few years of growing community mobilization, public outcry, round-table consultations, and coalition-based advocacy and organizing in Toronto and across the Greater Toronto Area, the Ontario government introduced province-wide regulations in 2015 aimed at eliminating carding and discriminatory targeting. My own participation in Ontario’s community anti-carding campaign allowed me to engage in a variety of forms of advocacy through policy submissions, media commentary, speaking engagements, and opinion-editorial writing. Though my primary point of entry was most often as a lawyer who saw the issue of carding through a legal lens enriched by a critical race analysis, I also appreciated the opportunities I had to work with and advocate on behalf of members of the African Canadian community in different and dynamic ways.

While the new laws are a step in the right direction, there is still work to be done. Police carding continues, in different forms and in the same old ways, mainly on Toronto Community Housing properties, which exempt officers from the recently passed carding regulations. But when I reflect on what we have achieved so far and how I plan to continue to work on this and other issues of anti-Black racism in Canada, there’s one thing I know will serve me best: Sticking to my vision.

Anthony Morgan graduated from Trinity College’s Ethics, Society & Law program in 2008. He went on to pursue an LL.B and B.C.L. from McGill University’s Faculty of Law. Shortly after becoming a lawyer in June 2013, he drafted the Universal Charter on Media Representations of Black Peoples. The Charter was drafted as a tool for public education and awareness on the impact of the media on Black lives and experiences, as well as a tool for community organizing and advocacy against all forms of anti-Black biases and racism in the media. Morgan’s commentary on social justice issues has been featured in the Globe and Mail, National Post, Toronto Star, Huffington Post Canada, and other major newspapers and broadcast outlets, including CNN. The recipient of numerous leadership and advocacy awards, Morgan is also a 2016 recipient of a Lexpert Zenith Award for his contributions toward achieving diversity and inclusion, both within the legal profession and in society. In June 2016, Canadian Lawyer magazine nominated Morgan as one of Canada’s top 25 most influential lawyers.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.