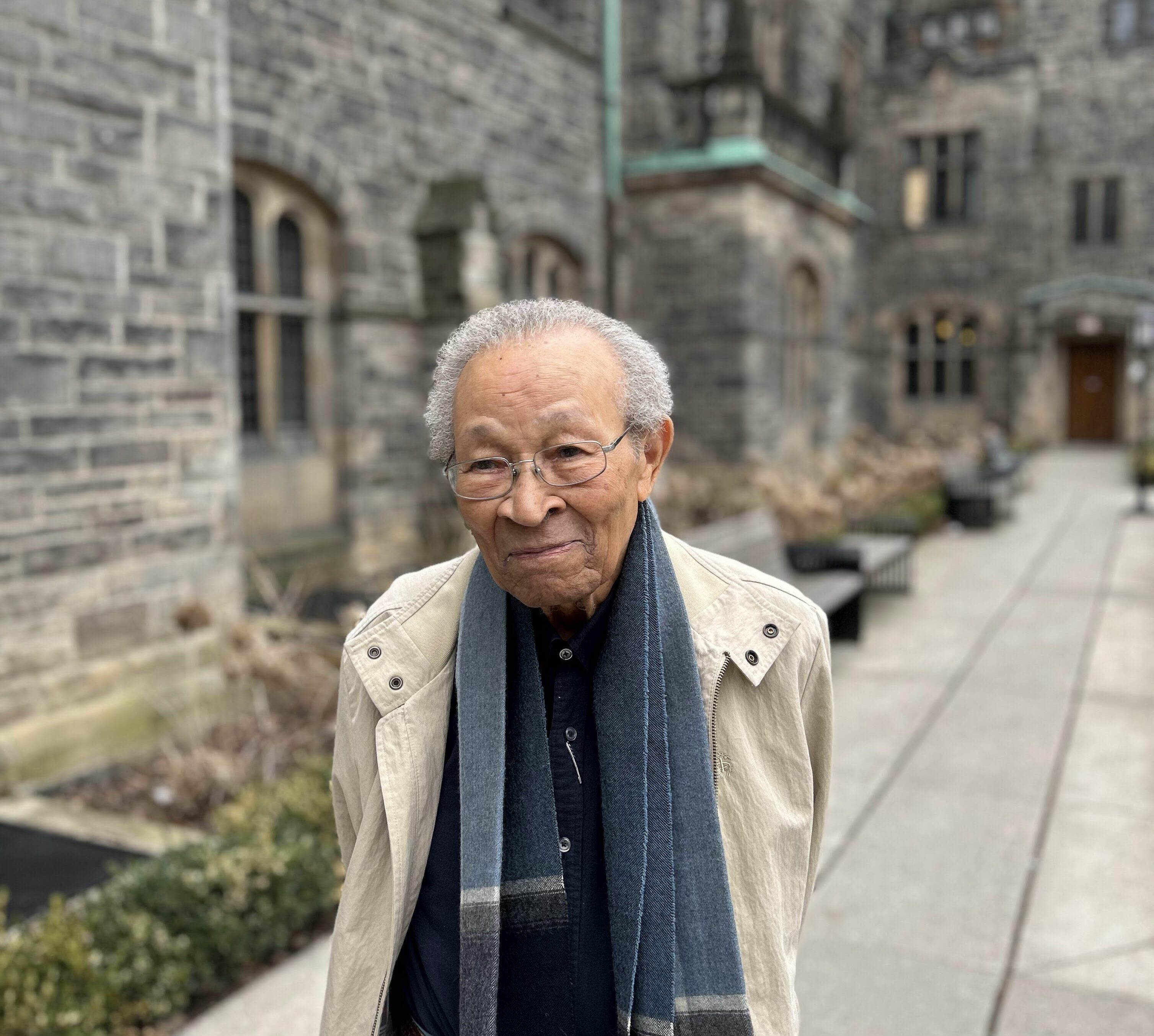

From student debates in the Lit to landmark inquiries and courtroom decisions, Keith Hoilett ’60 has lived a life rooted in reflection, principle, and quiet leadership. At 92, this vital alum continues to play his hand—in bridge and in life—with the same grace and clarity that guided his judicial career.

By Jennifer Matthews

The Honourable Keith Alexander Hoilett ’60 arrives at Trinity College directly from his weekly bridge game at the Royal Canadian Yacht Club, just a few blocks away—a ritual that connects him to his student days in ways both profound and practical. At ninety-two, Justice Hoilett walked the four kilometres from his home near the St. Lawrence Market in Toronto to the Royal Canadian Yacht Club for his weekly game, then walked over to Trinity for our interview.

Following our three-hour conversation, he stood up and prepared to walk home, embodying the same discipline and vigor that characterized his remarkable legal career, which spanned more than six decades.

The bridge game is a tradition stretching back to his Trinity days, when he and five roommates played in residence, eager to finish dinner in Strachan Hall early and claim a table in the common room. “Bridge teaches you to count, to listen, and to wait your turn,” he reflects. “That’s not a bad foundation for life.”

From Jamaica to Trinity: Early foundations

Born in rural Jamaica in 1933, Hoilett grew up with the expectation that he would strive, achieve, and contribute. He attended Excelsior High School in Kingston before immigrating to Canada at 22. Drawn to Toronto as a cosmopolitan centre and to Trinity College for its Anglican foundation, he began his undergraduate degree in political science and economics in 1956. “Religion wasn’t my driver,” he recalls, “but the idea of a place rooted in values was appealing.”

His arrival at Trinity was a dramatic shift in worlds: “I came from poverty into a cradle of privilege,” he says, candidly. And yet, he quickly found his place, immersing himself in college life. He pursued a degree in political science and economics, but it was his involvement in the Trinity College Literary Institute—known as “the Lit”—where Hoilett truly found his voice. The oldest university debating society in Canada, the Lit in the 1950s offered what many students later described as a formative experience, providing leadership opportunities and a sense of community. Here, Hoilett’s debating skills flourished; by his final year, he had been elected Speaker of the Lit, a position that would prove prophetic for his future career in law.

Formative friendships and faculty mentors

A favorite anecdote involves Dean Allan Earp, who wrote to congratulate him on his Lit appointment. “The Dean was pleased about my new role,” Hoilett chuckles, “but he also took the opportunity to remind me not to leave coffee cups on windowsills. That was Trinity for you—they celebrated your achievements and kept you grounded at the same time.”

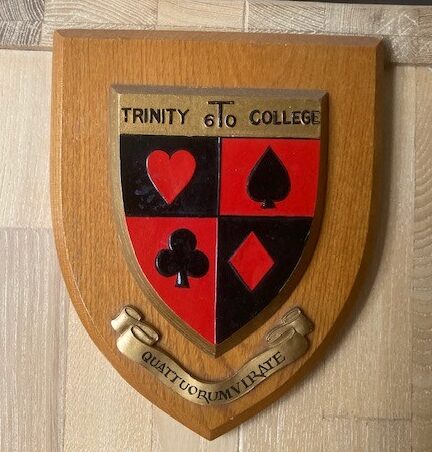

His Trinity friendships have endured. He and five roommates formed a bridge-playing cohort known as the “Quadrumvirate,” complete with a custom-designed crest featuring card suits and the Trinity lion. “We shared rooms, meals, bridge games, and years of growing up,” he says. Many of them remain in touch, including John Swinden ’60, Peter Farwell ’59, Burn Creeggan ’60, Henry Gladney ’60, and Ken Langdon ’60, who later joined him on the bench.

Hoilett also maintained contact with John Goodwin ’57, who went on to become one of two deputy governors at the Bank of Jamaica. He fondly remembers former Trinity Chancellor Bill Graham ’61, who served as president of the Lit during Hoilett’s tenure as Speaker.

A legal career rooted in reason and fairness

After graduating from Trinity in 1960, Hoilett continued at U of T for law school, completing his degree in 1963. He articled at Thomson, Rogers, a Toronto law firm where he gained valuable litigation experience that would serve him throughout his career. But it was his decision to join the Crown Attorney’s Office in 1966 that truly launched his public service career.

For nine and a half years, Hoilett prosecuted criminal cases, developing what colleagues described as an exceptional reputation for good judgment and professionalism. “Criminal law teaches you to deal with human nature at its most complex,” Hoilett observes. “Every case involved real people facing serious consequences. I learned that justice isn’t just about applying the law—it’s about understanding the human dimension of every legal decision.”

In 1975, he became the first employee of Ontario’s newly created Ombudsman’s Office, under Arthur Maloney. There, he helped shape a new institution meant to protect fairness in public administration.

One of Hoilett’s most significant contributions was leading the North Pickering Land Inquiry over four years, investigating controversial land expropriations. “It was about people’s dreams,” he says. “Government decisions had disrupted lives. The least we could do was listen and report with integrity.”

Appointed to the bench in 1981, Hoilett served as a County Court and later Superior Court judge for 27 years. His judicial philosophy centered on fairness, restraint, and clarity. “I never wanted to play God,” he says. “Judgment is difficult. It demands humility.”

A voice against labels

Throughout his life, Hoilett has resisted racial and political labels. He declines invitations to speak on the “Black experience” in Canada, preferring to share his personal story. “I’m not a label,” he says. “Describe my journey, my ideas, my work. Let that be enough.”

He is candid about privilege, injustice, and the dangers of capricious memory, telling stories not to dramatize, but to illuminate. “I believe in a just society with room for all of us,” he says. The challenge is to make spaces whereby we value each part without destroying any of them.”

Life in Toronto

Justice Hoilett remains intellectually engaged and continues his weekly bridge games, viewing them as both recreation and mental exercise. “I can’t understand boredom,” he quips, adding that he continues to receive two newspapers each morning. “What makes life interesting is having an unquenchable curiosity. I have a reason to get up and smile every day.”

Living near the St. Lawrence Market in Toronto, he enjoys his proximity to both the market and the nearby Distillery District. His preference for walking whenever possible exemplifies his commitment to staying active and engaged with his community—whether it’s the four-kilometre walk to his weekly bridge game or simply exploring the vibrant neighborhoods around his home.

His family, including children Philip and Sarinda and three grandchildren, remain central to his life. “I am happy to share what I’ve learned with them, but I’ve always believed in the importance of education and encouraging young people to pursue their own paths,” he says.

Words of wisdom

When asked about the advice he would offer today’s students as he approaches his 65th reunion at Trinity, Hoilett returns to themes that have guided his life and career. “You don’t get education from textbooks. Education comes from life. Take advantage of every opportunity to engage with ideas and people different from yourself,” he counsels.

“Trinity gives you that opportunity in a supportive environment. The friends you make and the skills you develop—whether in debate, in leadership, or simply in learning to think critically—will serve you throughout your life.”

“Most importantly,” he adds, “remember that education is not just about personal advancement. It’s about preparing yourself to contribute to your community and to make a difference in other people’s lives. That’s what Trinity taught me, and it’s a lesson that has guided everything I’ve done since.”