By Michah Rynor

Each fall, the Trinity campus is flooded with new people. The hallways are a constantly changing landscape of faces and conversations, as a new generation of students begins its own post-secondary journey.

Observing this dynamic scene year after year are the touchstones you remember from frosh days. Stone and metal sculptures remain perfectly still and perfectly present. It’s an art collection that remains one of the great assets of not only the College but of Canada itself.

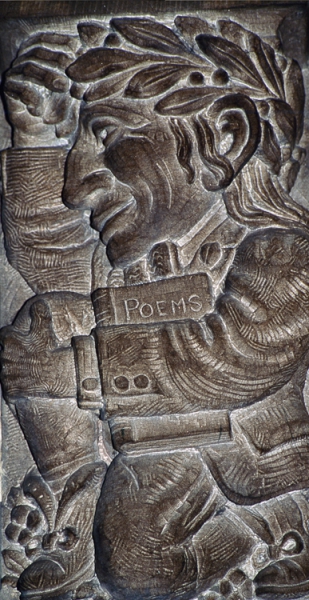

The laurel-wearing poet (figure 1), the theologian clutching scrolls, the philosopher with his keys of knowledge and the horsehair-wigged lawyer (figure 2)—they may be carved in stone but they’re among the first “people” to greet visitors arriving in Trinity’s grand lobby.

“Come here if this is what you’d like to be,” they silently advise. Astonishingly, these highly detailed and characteristic portraits (called “corbels” by architects), are anonymous and not, as many have long thought, celebrated Trins (although a few students over the years firmly believed the philosopher was former professor and literary icon Robertson Davies).

And yet, the talented man responsible for these beloved—and slightly humorous—heads, Charles Adamson, never saw himself as an artist but merely as someone who carved stone.

“His work is very distinctive,” says Sylvia Lassam, Trinity’s Rolph-Bell Archivist for the past decade. “They’re not entirely serious and they’re not entirely humourous. They’re caricatures but they’re not disrespectful or mean-spirited in any way.”

Lassam loves the whimsical nature of these elders who have stood guard for so long. “They make me smile. They’re not necessarily what you’d expect to find in such a serious-looking building.”

Trinity is full of such enigmas and one of the strangest puzzles lies right beneath these four wise men—a complete set of zodiac figures arched around the wooden doors leading to the quadrangle (figures 3 & 4).

The use of zodiac symbols is frowned upon in many academic circles and places of worship.

“Unfortunately, the records of architects Darling and Pearson didn’t survive and so we may never know why an astrological motif was added,” Lassam explains of this celestial mystery. “It’s not unprecedented in medieval art but it seems an odd choice for Trinity College.”

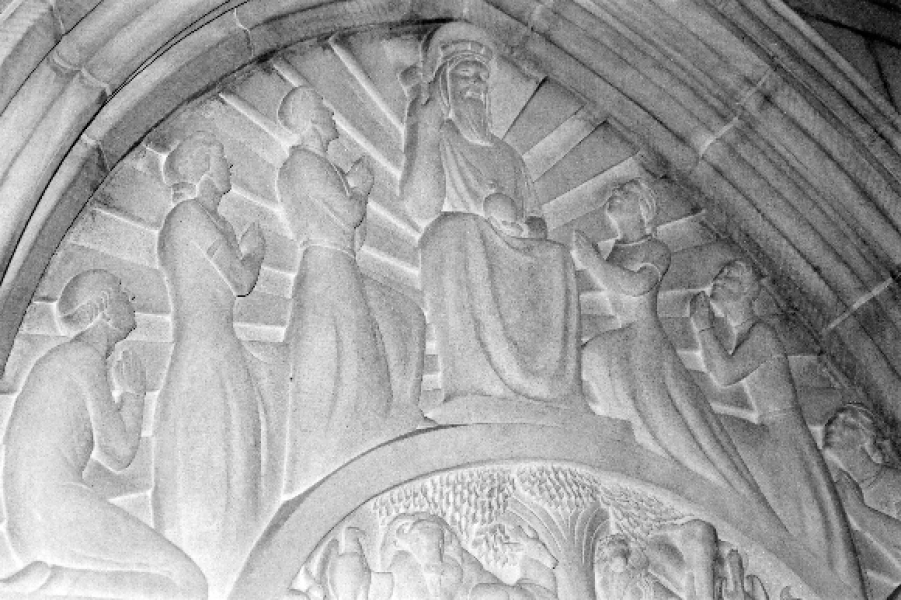

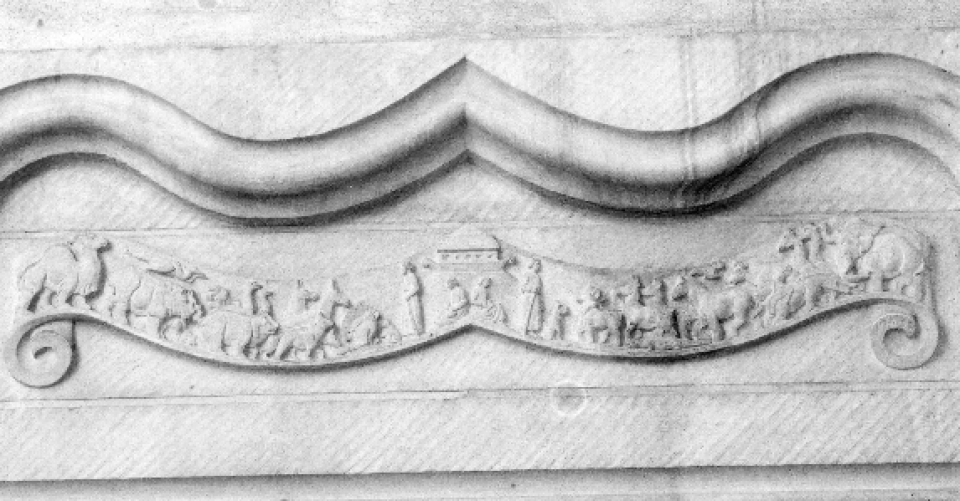

The celestial theme continues in “God of the Universe” on the wall of the Trinity Chapel’s nave (figure 5). It’s a favourite of those who admire the Art Deco movement and its effect on the paintings, sculptures and architecture of the 1920s and 30s—even though its creator, the acclaimed Jacobine Jones (the only female sculptor represented at Trinity), began chiseling away at it in 1957. Close by is Jones’ “Noah’s Ark,” (figure 6) a whimsical necklace of a piece on one of the church’s lintels (architectural elements found above doors and windows). With Jones’ collection of animals on the ark and the corbels that line the hallways of the main floor, Trinity is a veritable zoo!

The corbels—artistic sculptures that symbolically support Trinity’s hallway arches and ceilings—consist of scores of mammals, birds, fish and lizards—all carved decades before Jones created her own stone menagerie. At first glance, these corbels on the west side of the main floor are simply delightful renditions of ordinary animals. Look closer and a different reality emerges.

In most of these scenes, the creatures are in an aggressive mood—a heron taunts a duck with a fish (figure 7), an iguana grapples with a horse (figure 8), a donkey appears to threaten a duck (figure 9), a mouse scolds a cat (figure 10), a mother robin arrives at her nest to find a squirrel eyeing her newborn chick and a plump egg (figure 11), a wolf and a buffalo are about to come to blows (figure 12), a moose advances on a frog (figure 13), a dog has a walrus by the tusk (figure 14), and an owl delivers a swift kick to a duck (figure 15).

Was the carver of all this mayhem trying to convey a subtle message to the students? That uncivilized nature is a place of savagery as opposed to the enlightened world of academia and religion? Or perhaps, as some have proposed over the years, the carvings are simply humourous cartoons not to be taken too seriously.

“The architect, John Pearson, was known to like showcasing Canadian flora and fauna,” Lassam states. “In the 1920s there was a newfound nationalism—especially after the First World War when historians believe we really became a country in our own right. Canadians were extremely proud of their identity so it might be that Pearson was simply creating elements from nature that he felt needed to be included in a Canadian academic building, just as he did when working on Ottawa’s parliament buildings.”

In any case, these kinds of naturalistic corbels are unique and stand in stark contrast to the ones lining the east side of the floor. Here, the world of sports is highlighted with hockey, hunting, football, skiing, fishing, baseball and cricket as inspiration. An interesting observation of the sculpted artworks dotting the building is that, for such a monarchy-loving era, animals, athletes, religious figures and anonymous men far outnumber stone visages of royalty.

In fact, there are more carved birds at Trinity College than there are members of the royal family with only one king and one queen represented—(George VI and Elizabeth) whose calm, youthful faces have witnessed every outdoor quad party and under-the-stars theatrical production since 1926.

Seeley Hall, for years the College’s chapel, was supposed to be the library, which explains why carvings of men and women—who may or may not be literary figures—line both sides of the room.

“We don’t know who these figures are but it wouldn’t surprise me if some day a book of legends that features these actual faces is discovered,” says Lassam. “I suspect there was a published source used by the carvers and so we could have Robin Hood up there or King Arthur. The inspiration for these characters could even be from an abbey in England or a cathedral in France so I’m moderately hopeful that someday we’ll find out now that so many images are posted on the internet.”

But not all touchstones are made of granite. In 1962, the north wing of the quadrangle was finished with the addition of Cosgrave and Seager Houses. Harold Stacey, a celebrated sculptor, was brought on board to create metal artworks to adorn the dormer windows—sculptures that are not, as some have long believed, lightning rods.

A rooster represents the provost of the time (Francis Cosgrave); an antelope is copied from Bishop Seager’s crest; the head of a boar comes from Graham Campbell’s coat of arms (then Chair of the Executive Committee); a tricorne hat (sometimes mistaken for a three-cornered pirate’s chapeau) symbolizes the College’s literary institute; a mitre symbolizes the founder of Trinity, Bishop John Strachan; and a hound (or “talbot”) forms part of benefactor Gerald Larkin’s coat of arms. And it is here that yet another mystery crops up.

One window pinnacle has been missing its burnished sculpture since the 1960s—the cryptic bronze skull atop a set of keys, which represented a once-respected—but now banned—student group. Presumably stolen in the dead of night, it has never been found—although in 1984 a psychic contacted the College saying she could find it. Alas, it remains absent to this day.

Another rooster, honouring Provost Derwyn Owen, adorns the entrance to the residence named for him while a lion, representing Provost Cosgrave, guards the residence that bears his name. Through most of the 1990s, the lion had a knife and fork placed in his paws (arranged decoratively by a mischievous student) and a cloth napkin knotted around his mane. Students—and faculty—were surprised that no one took these accessories away and that the snarling beast remained High-Table-ready for years.

While these sculptures represent a modern approach to sculpture compared with the traditional stonework, many view the most modernistic of the metalworks as the 1962 bronze piece by Gerald Gladstone, “Solar Net,” which floats over the entrance of the Gerald Larkin building.

Gladstone’s swirling mass of steel was inspired by his belief that the machine was “the most formidable symbol in contemporary society… a basic form of survival which forces man to a more logical place in the scheme of things.”

Birds, however, see Gladstone’s piece as a “solar nest,” which requires maintenance staff to ladder up annually to remove the masses of twigs and feathers that become matted throughout this complex artwork.

Feather retraction is just one of the many challenges Tim Connelly, Director of Facility Services, and his team face.

“We use a restoration company that employs experts with many years of experience but it’s getting harder to find such tradespeople as they’re getting on in years,” he says.

Connelly, who considers himself just one of many who zealously guard these wondrous works, reaches out to colleagues, contractors, experts in the field and his Trinity predecessors.

Metalworks, he points out, need the right kind of paint to protect them from oxidization, intense ultra-violet light, rust and moisture.

“With stonework, the main culprit is water seeping in. Pollution in the air is a factor as well so gentle cleansing of the art is a must.

“Trinity wouldn’t be Trinity without these beautifully rendered works and so we take great pride in caring for them,” he says, adding that the College invests heavily in making sure that all who visit the campus will continue to be greeted by wise elders, cricket players, birds and bees, lobsters, bears, moose and anonymous faces from the past.

“What amazes me is the great care and attention that was taken to create a beautiful College,” says Lassam. “The administration thought that students should be exposed to well-designed, lovely things. Trinity has always been inspirational—these works offer students great art as one more source of that inspiration.”

test

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.